The high point of next year’s Hong Kong Arts Festival is a long-overdue appearance by Moscow’s renowned Bolshoi Theatre. Three programmes, including two major works never seen here before, promise a visual, dramatic and musical feast.

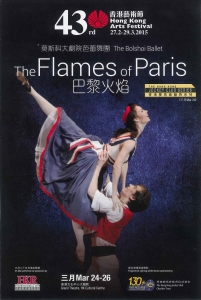

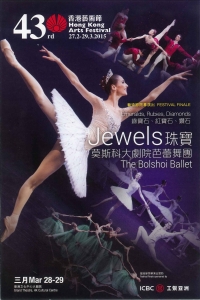

Jewels The Flames of Paris

The Bolshoi Ballet brings two contrasting productions. The first is the Hong Kong première of Alexei Ratmansky’s Flames of Paris, a grand spectacle set during the French Revolution packed with the flamboyant virtuoso dancing which is the company’s trademark. The second, last performed here by the Mariinsky (then Kirov) Ballet in 2002, is George Balanchine’s elegant plotless masterpiece Jewels. Both feature numerous solo roles, giving audiences the chance to see many of the troupe’s exceptional current crop of stars.

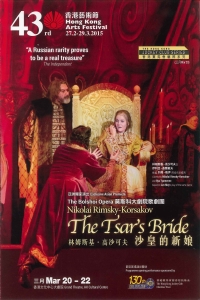

The Bolshoi Opera is the keeper of the flame of Russian opera, preserving and renewing its greatest traditions. Local opera lovers will remember the superb performances of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov and Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges on the company’s last visit in 2002.

In 2015 the company is bringing something very special - the Asian première of Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1899 The Tsar’s Bride (Tsarskaya Nevesta), under the baton of one of the world’s greatest conductors, 83 year old Gennady Rozhdestvensky.

Based on a notorious historical mystery, this is the composer’s most popular opera in his home country yet until recently was rarely performed outside Russia. Today it’s one of the opera world’s hottest properties with a first-ever staging by the Royal Opera at Covent Garden in 2011 and a joint production by La Scala/Staatsoper Berlin in 2014. So this is a golden opportunity for Hong Kong audiences to see why it’s been causing such a stir.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) was one of a group of Russian composers, including Mussorgsky and Borodin, whose aim was to move away from existing European conventions and produce music which was intrinsically Russian in character. Famed for his rich, gorgeously-coloured orchestration, Rimsky-Korsakov composed some 15 operas - best-known internationally are those based on Russian fairy tales like Sadko, The Invisible City of Kitezh and The Snow Maiden.

Dark and intense, The Tsar’s Bride is very different in style both dramatically and musically.

The story is based on a historical episode. In 1571 the twice widowed Tsar Ivan IV (Ivan the Terrible), selected a new wife, 19 year old Marfa Sobakina. Almost immediately, Marfa was stricken by a sudden illness and 2 weeks after her wedding she died.

What caused her death remains unknown - rumour had it at the time that it was a fertility potion provided by her mother. As for the increasingly paranoid Ivan, true to form he assumed she had been poisoned by his enemies, executed anyone he thought might be responsible and six months later had married a fourth wife.

Lev Mey’s play The Tsar’s Bride, on which the opera is based, imagines an elaborate solution to the mystery which mixes historical characters with fictional ones.

Grigory Griaznoy (the name resembles the Russian word for “dirty” and “Dirty Greg” is certainly a fitting sobriquet) is one of the oprichniki, the infamous band of thugs who act as the Tsar’s secret police. He secretly loves the pure, innocent Marfa, who is betrothed to her childhood sweetheart, Ivan Lykov.

Griaznoy obtains a love philtre from the venal German physician Bomelius which will make Marfa fall in love with him instead of Lykov. Gryaznoy’s mistress Lyubasha, consumed by jealousy, asks Bomelius for a potion to destroy Marfa’s beauty - she’s so desperate she agrees to his demand that she sleep with him as payment - which she substitutes for the philtre.

Marfa is among the candidates to be the Tsar’s new wife but when it seems that his choice has fallen elsewhere, she and Lykov joyfully celebrate their engagement. Gryaznoy slips what he thinks is the philtre into Marfa’s glass. No sooner has she drunk it than a messenger arrives to announce, to everyone’s consternation, that it is she who has been chosen as the Tsar’s bride.

The final act takes place two weeks later in the Tsar’s palace where Marfa lies desperately sick. Gryaznoy tells her that the Tsar has had Lykov put to death for poisoning her - Gryaznoy himself killed him. In a mad scene reminiscent of Giselle Marfa loses her mind, retreating into a fantasy where she and Lykov are together and taking Gryaznoy for Lykov. In despair Gryaznoy confesses it was he who poisoned Marfa but Lyubasha reveals that the poison came from her and tells Gryaznoy to kill her. He stabs her to death and is led away to be executed as Marfa dies, with her last breath asking her beloved Lykov to visit her again next day.

From this melodramatic material, Rimsky-Korsakov fashions a raw, visceral drama where the portrayal of the darker characters is particularly powerful. Gryaznoy and Lyubasha are both complex, psychologically convincing individuals who provoke our sympathy despite the terrible things they do.

Lurid though the plot may be, The Tsar’s Bride paints a compelling picture of a world without the rule of law, where the will of the Tsar and the brutality of the oprichniki hold sway. While Ivan makes only a brief appearance, his shadow looms over the story. The deaths of Marfa and Lykov may be caused by Gryaznoy’s obsession with Marfa (and Lyubasha’s with Gryaznoy), yet it’s the Tsar’s despotism which takes them from each other. Rimsky-Korsakov was a lifelong liberal and these themes remained relevant to the Russia of his own time, as indeed they do today.

Musically, the score follows a more “Italian” pattern than most of the composer’s operas, with a classic structure of overture, arias and ensembles. Nonetheless the music remains infused with a Russian flavour, notably in the thrilling choruses. Rimsky-Korsakov deliberately avoids the bel canto flourishes of Verdi or Puccini, creating a realistic music drama which foreshadows 20th century operas by the likes of Shostakovich or Britten. Bold strokes include Lyubasha singing her haunting opening aria unaccompanied and the opera’s low key ending on Marfa’s dying words.

The Tsar’s Bride has always been a staple of the Bolshoi’s repertoire - its 1955 production, performed for over 50 years, was long the opera’s benchmark. The current staging by acclaimed Russian-born director Julia Pevzner, which dates from 2012, offers a fresh look at the drama combined with lavish sets and costumes which evoke the rich colours of 16th century Russia.

With Rozhdestvensky, a cast of rising stars and the magnificent Bolshoi orchestra, The Tsar’s Bride is not to be missed by anyone interested in opera or Russian music.

About the author: Originally from London, Natasha Rogai has lived in Hong Kong since 1997. She is the dance critic of the South China Morning Post and Hong Kong correspondent of Dancing Times. She is also Vice-Chairperson of the Hong Kong Dance Alliance.

Photo: Hong Kong Arts Festival