Ask Akram Khan the questions “Who are you? Where are you from?” and perhaps DESH is what you will get as an answer. Akram Khan’s latest solo piece is a complex set of personal narratives weaving together layers of reality and imagined time and space. The breathtaking 80 minutes of dance, display of multimedia animations, fairy-tale narrations, conversations, monologues…all come together to express the choreographer’s questions of identity in the age of globalization and deep down, his yearning for his “home” country Bangladesh.

A second-generation immigrant in the United Kingdom, Akram Khan was born in London into a family of Bangladeshi origin. He is renowned for his wonderful fusion of Kathak, a traditional Indian form of dance, into contemporary dance choreography, and though this particular piece does not refer specifically to this feature, traces of his Kathak training, like rhythmic footwork and rapid spins, can still be found.

DESH is a story about proximity and distance, connections and divisions, and a daring one that deals with multiple gaps in identity, generation, national history, technology, geography, language and culture. Khan manages to present all these serious issues with fantastical, child-like quality, making the performance highly enjoyable and intellectual at the same time.

In one of the beginning scenes of the show, Khan captures the spirit of his father through bowing down his bald head and revealing the ink-drawn face on top, at once playful like a kid’s game. He continues to play around with articulate hand-gesturing and precise neck movements rather cleverly and makes it highly believable for the audience that this face is really his father’s face. Khan also imitates his Bangladeshi accent and speaks of his conservative old ways, and contrasts that with his British accent and love for popular culture, perhaps most exaggeratedly demonstrated through his Michael Jackson moves. The personification of the father, however, is not just for comic effect. The bowed head signals at his lowly social status as an immigrant, and the repeated references to the father’s short height also work to the same effect. There is a hint of wistfulness as the audience gradually learns of the father’s struggles and how hard it must have been for him to leave his homeland to make a living to support his family. The father laments that Khan has not yet seen his own motherland and does not really understand Bangladeshi culture, but while the differences are crystal clear between Khan and the father, that is not the only generational gap we see.

Khan also includes the voice of his niece, Eshita. This young child of the third generation serves to reveal even further the loss of Bangladeshi tradition and knowledge as younger generations find themselves more British than Bangladeshi. It is certainly a wonderfully funny moment when Eshita asks if Khan’s story about a goddess in traditional folklore is like Lady Gaga, but no doubt it is also sad because the child does not see the value in learning about stories from their distant “home”. Poignant it is when the story Khan tells begin to melt into a most spectacular animation sequence narrating the folklore as Khan travels and dances through it, both as a young boy presented onscreen and as himself, as if he is momentarily transported to the lands of Bangladesh. It is perhaps only through his imagination that he can “return” to his “homeland” as the young boy, and see the beauty behind the motherland and learn of its enchanting tales and legends through innocent eyes.

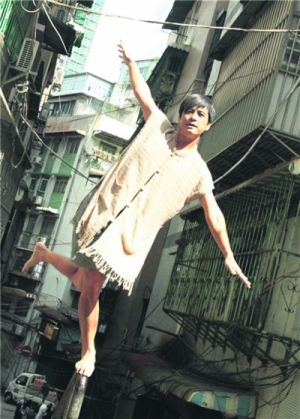

Khan’s yearning for the motherland is strongly conveyed in most parts of the narrative, and one of the most touching moments comes when once again Khan is seemingly transported into the imagined world of Bangladesh. Khan hangs upside-down, swaying endlessly amongst long thin strips of fabric that have filled up the entire stage space, slowly lowered from above. It is, perhaps, a romantic depiction of the fields of grass at “home”, as his father has described it…grass so tall that it looks as if “they grow from the sky”…and in this fantastical scene, Khan is swimming in it, floating in it, rolling and frolicking, as if he finds himself standing in vast fields for the first time…Visually stunning, it is a spectacle of the imagined, the surreal, that may even be said to be slightly ironic, where the audience, not unlike Khan, also imagines him swaying in fields of grass, knowing very well that it is constructed, created, represented on stage and nothing more than a figment of imagination.

This piece of land is far away from him, perhaps too far even, and Khan cannot “completely” become Bangladeshi and connect to this piece of homeland because as much as he is, of blood, he is also British, through the upbringing and education he had, and these are all aspects of his identity that he embraces and has to embrace. How distressing is it that we are shown Khan’s connection to this “home” country is through the Apple Care service hotline that got rerouted there? And that these scenes of “Bangladesh” and depictions of its culture inside the performance are created from his imagination as he has never set foot in the country?

If you ask me the questions “Who is Akram Khan? Where is he from?”, this would be my reply — Akram Kah is a storyteller, a highly-imaginative and creative one, and his body, with its ethnic marker, is the medium through which untold stories of generations of migrants living in diasporic existence are told. DESH is a story of one man’s journey for his roots, and is one story that will touch many hearts as Akram Khan brings this outstanding piece of art to different theatres in the world.

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。