2024年11月

Theater programs vary in form and function across different regions of the world. As they are predominantly recognized today in most Western countries – or Westernized societies, such as Brazil – their origins can be traced back to the 19th century, when rudimentarily printed pamphlets listing authors and cast members were distributed to patrons before the shows. Since then, they have gained complexity and evolved into a textual genre of their own, standing as integral components of the spectatorial experience and serving as tangible connections between audiences and the inherently ephemeral nature of live performances.

Primarily, programs offer essential information about productions, with variable degrees of detail about the identities and backgrounds of playwrights, directors, producers, actors, and the many professionals responsible for lighting, scenography, sound design, makeup, costumes, and other scenic elements. Although they should not, as Patrice Pavis contends[1], dictate or predetermine reception, they operate as paratextual devices and may shape spectators’ horizons of expectations. Commonly enriched with critical articles, commentaries, interviews, and photographic essays especially produced for their pages, they cast light on particular aspects of the creative, formal, and aesthetic configurations of shows, as well as on their cultural, political, and historical imbrications. In these booklets, even advertisements constitute potential ingredients for investigations into the socioeconomic dimensions of the arts, patterns and modes of funding, and contemporary trends of consumption.

Beyond these immediate informative and formative purposes, programs possess enduring value for retrospective analyses of performances, allowing for their reassessment within their original contexts. Their indispensable place in archives, libraries, and documentation centers contributes not only to the preservation of the memory of performing arts, but also to the emergence of new perspectives in criticism, history, and historiography in the field. Additionally, both theater enthusiasts and critics often keep them as cherished memorabilia, attesting to their personal engagement with the stages over the years.

As a researcher affiliated with the Center of Theatrical Documentation of the University of São Paulo (Centro de Documentação Teatral da Universidade de São Paulo)[2], I have recently witnessed the donation process of nearly 5,000 programs to their collections. Spanning from the 1940s to the present, this assemblage belonged to José Cetra Filho, a theater critic based in the city of São Paulo who methodically combined the keepsakes of performances he attended for decades with rare programs of Brazilian canonical productions gifted to him. After being properly cleaned, organized, cataloged, and stored, they will be made available for public consultation, joining thousands of other programs housed on-site. Reflecting on the transfer of 18 large boxes from the shelves of his living room to one of the most renowned universities in the Americas, Cetra Filho remarked in a lamenting tone: “With digital programs everywhere now, collections like mine will soon cease to exist…”

His nostalgic words immediately captured my attention. They echoed the growing whispers of discontent I have been hearing each time I go to the theater in São Paulo and encounter a poster with a QR code where few years ago printed programs would be distributed. “Oh no, not another digital program!”, mutter those who pass by, outwardly rejecting the technological resource, and others who resignedly download more content to their smartphones, adding it to the ever-multiplying gigabytes of apps, photos, and cache files.

The growing ubiquity of digital programs, from grand productions to more modest ones, has largely been framed as a creeping threat to the very ritual of spectatorship, initiated by the pleasure of flipping through visually appealing pages and sealed with a palpable souvenir.

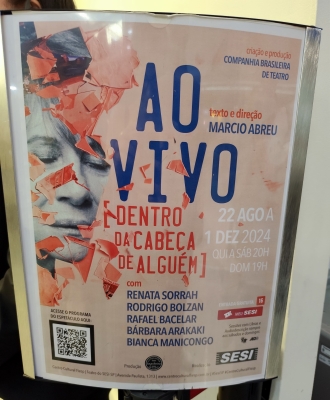

Left: Poster of Prima Facie, written by Suzie Miller and directed by Yara de Novaes, currently showing at Teatro Vivo, in São Paulo;

Right: Poster of Ao vivo dentro da cabeça de alguém, written and directed by Marcio Abreu, now showing at Teatro do SESI, in São Paulo

Both productions offered exclusively digital programs, accessible via QR codes at the bottom of the posters (Photos: Esther Marinho Santana)

Dissatisfaction seems to extend beyond the general audiences. In local academic events devoted to discussing archival practices for the performing arts, variations of a sentiment intertwining anticipatory grief and epistemological disorientation are abounding. How should we interpret the increasing popularity of digital programs? Will they entirely replace printed booklets? Can the life of our contemporary stages be efficiently preserved through digital mechanisms? Will collections neatly curated and exhibited on bookshelves, either in private or public archives, eventually coexist with a myriad of icons and weblinks on computer screens? Would data in the computational realm intensify or counterbalance the constant financial limitations faced by Brazilian institutions? In which ways must the conventions, terminologies, methodologies, and techniques that underpin documentation be adapted or reformulated to accommodate the accelerating reliance on virtual tools? As a medium that extrapolates the textual and iconographic bases that we have come to know, will digital programs produce new modes of reading and engaging with performances?

I do not intend to provide definitive answers to these questions here. Such rapidly shifting landscapes raise pressing inquiries that necessitate sustained, careful debates. Or, if you excuse my rather anarchic appropriation of T. S. Eliot’s lines, these matters demand space and time for “a hundred indecisions, / And for a hundred visions and revisions”. For now, I shall address what I consider the fundamental factors of this conundrum, embracing, instead of truly resolving, their tensions and contradictions.

Opportunities and Limitations to Creation, Dissemination, and Accessibility

Regardless of various sponsorship programs funded by cities, states, or the federal government, making theater and attending theater in Brazil have always been financially challenging. Admission prices are hardly popular and one ticket can cost as much as 10 percent of the national minimum wage. While in certain theatrical communities, such as England, programs tend to be sold, Brazilian audiences are unlikely to adhere to this additional expense, leaving all costs related to the production and free distribution of booklets to the venues, producers, or artists.

Printing high-quality, colorful materials at adequate resolution remains prohibitively expensive in most parts of the country. Digital programs have offset this obstacle by offering amateur or smaller groups the opportunity to have visually rich content that would otherwise only be affordable for productions with substantial budgets. Moreover, the advent of user-friendly free or low-cost applications has moderated the production dynamics of aesthetically refined programs. Even though the expertise of professional designers remains irreplaceable, many theater makers and companies cannot bear the costs of their services and find in these digital tools the means to create documents that meet satisfactory visual and informational standards.

Evidently capable of inaugurating new pathways and possibilities for content production and its immediate dissemination, digital formats also reveal great potential in promoting advancements in accessibility paradigms and inclusive communication strategies, particularly for individuals with visual impairments. Through integration of assistive technologies, digital programs provide detailed visualization via zoom functionality for both text and images, while complementary features like text-to-speech conversion facilitate engagement with written elements.

However, reliance on digital programs presupposes that if audiences wish to read them before performances, they will have smartphones or tablets with either access to reliable wireless internet connection provided by venues, or sufficient mobile data. These prerequisites are not always attainable, most notably in economically marginalized regions or towns distant from metropolitan centers.

Other structural social, cultural, and economic issues emerge as pertinent impediments to accessibility. Digital materials frequently impose barriers to elderly individuals – and they are certainly the bulk of those I observe walking away when faced with posters featuring QR codes. According to a 2023 survey conducted by the national public news agency Agência Brasil, our senior citizens still struggle to adapt to technological tools: despite representing the demographic segment with the fastest-growing internet adoption rates in the country, only 66 percent of this population currently go online[3]. Broader persistent inequalities in digital literacy, which extrapolate generational spheres, beg for consideration as well. Inhabitants of developing regions affected by low educational levels may possess limited capacity to effectively utilize technological devices for information retrieval, critical evaluation, comprehension, and dissemination. In these scenarios, digital programs are more likely to operate as restrictive rather than enriching components of the spectatorial experience.

Losses and Gains in Preservation and Presentation

It is not unreasonable to assume that all of us agree that the physicality of printed programs provides a unique embodied connection to performances, generating a material memory that digital counterparts are not able to replicate. We can thus conclude that personal collections are much more meaningful and attractive when they are formed by objects that can be sensorially explored through touch, texture, and even scent. Likewise, one of the major appeals of public collections is the fact that their items can be exhibited to viewers who rejoice in the very act of looking and consulted under specific criteria. Nevertheless, many institutions might have their conservational and dissemination functions benefited by digital items.

In spite of the notorious consensus that museums, libraries, archives, and documentation centers should constantly invest in optimized measures for the preservation and management of tangible heritage, the accidental fire that consumed 90 percent of the installations of the Brazilian National Museum in 2018, shows that this may not always be achievable[4]. Profoundly impacted by administrative negligence and the lack of adequate structures for decades, the institution continues to battle to gather sufficient public and private financial resources for its reconstruction. The complete destruction of many of its items, such as “Luzia”, a 11,500-year-old female skeleton, the oldest found in South America, exemplifies an irreplaceable loss that, one could argue, differs from a hypothetical loss of theater programs, since multiple copies of the same booklet are printed and distributed during a season, making their preservation in multiple places feasible. Even so, each collection is singular in its own institutional significance, curatorial organization, and its relation to other artifacts, whether housed in the same archives or elsewhere. The basic maintenance of buildings – which involves pest prevention, ventilation monitoring, and the upkeep of electrical, water, humidity, and fire systems – incurs vast expenditures that excel the budgets of many of our institutions.

The storage of digital documents, on the other hand, may be less costly, even if it comes with its own set of challenges, including financial ones. Difficulties begin with the variety of original formats used for digital programs, like PDF, HTML, JPEG or PNG, which complicate archival procedures, typically grounded in standardized codes, systems, means, and methods. This can eventually render consultation impossible due to technological obsolescence – many of us still remember, after all, the now-defunct Adobe Flash content. Institutions must also consider a basal matter: to ensure safe storage, i.e., protected from catastrophes that could lead to the destruction of their collections, should they develop new platforms, adapt their own existing tools, or purchase external professional solutions?

Whichever route is chosen, it will inevitably require specialized technical support to create redundant systems and manage storage capacity, regular backups, checksums to detect file corruption, software updates, security patches, hardware upgrades, protection against cyberattacks, and the migration of data to newer formats or systems over time. What is more, platforms should be user-friendly, catering to both experienced researchers and the general public, and accessible across different devices and operating systems.

When properly administered, digital platforms not only guarantee unparalleled levels of integrity and longevity of collections, but also facilitate data and information sharing in ways that traditional physical documentation cannot rival. Archival centers may work on establishing interoperability – that is, the ability for different systems and platforms to work together – through APIs (Application Programming Interfaces). APIs serve as bridges between software systems, allowing them to communicate and exchange data, and institutions in different regions of the same territory, or even around the globe, can use them to connect their databases, enabling professionals and users to access and cross-reference materials from multiple sources without the need for costly and time-consuming travels. This is a particularly advantageous idea in countries like Brazil, the fifth-largest country in the world, where the majority of libraries and documentation centers are concentrated in one single area, the historically privileged Southeast. Ultimately, this lively ecosystem fosters fruitful conditions for more critical analyses and for the creation of collaborative networks on both national and global scales.

Towards More or Less Sustainability?

One of the most repetitively cited arguments in favor of digital programs is their environmental benefit. Like the long-standing debate over the advantages and disadvantages of e-books has posed, printed materials consume a great number of natural resources, like water and timber for paper production, as well as raw materials for ink manufacturing. Fundamentally, by reducing the demand for paper, forests are preserved and play a crucial role in protecting biodiversity and sequestrating carbon. Physical books also generate high carbon emissions due to their lifecycle, from the processes of printing, packaging, and transportation to the distribution to theaters. And well, let us be honest, we all know that it is not uncommon for theatergoers to discard their programs after performances, generating waste that may or may not be recycled, depending on varying local legislations and practices.

As Robert Rattle demonstrates in Computing Our Way To Paradise?[5], though, the belief that technology can inherently create a greener future is problematic, to say the least. Digital documents have their own environmental costs, since in order to be downloaded and accessed, they require smartphones, tablets or computers, which rely on electricity. Furthermore, the content itself is stored and hosted on servers and data centers that consume considerable amounts of energy by needing constant cooling and maintenance, potentially offsetting the perceived benefits of going digital. While Brazil’s energy sector is primarily powered by renewable sources, mainly hydropower, and is one of the least carbon-intensive in the world[6], most countries still rely heavily on fossil fuels, making the digital realm more or less sustainable depending on different locations.

Same Old Practices vs Novel Modes of Engagement

Nowadays, digital programs in Brazil predominantly function as practical, low-cost alternatives to printed booklets, replicating their structure to such an extent that they appear to be their mere scanned copies. In other words, they are constituted by the same elements that compose paper programs, presenting no significant innovations in their form or content. The digital universe offers unique possibilities that beg to be better explored, such as the integration of audiovisual elements through the use of embedded video clips, audio files, and animations, which are able to create a multi-sensory reading experience. Additionally, hyperlinks to external sources, including related books and articles written by specialists and information on other performances, may provide much more comprehensive and diversified materials than the limits of printed pages permit.

This profusion of intertextual possibilities enables more nuanced reflections not only on the works of those immediately involved in bringing performances to life, but also on broader previous and derivative issues. In this vein, shows based on classical plays or foreign theater undoubtedly benefit from hyperlinked contextual materials that elucidate their original context and reception, how changes have or have not been made to different adaptations over time, as well as their acclimation to varied cultural and linguistic communities. Such curation holds special significance in regions affected by precarious educational levels, as it democratizes access to knowledge traditionally reserved for academics or theater professionals, thereby inaugurating opportunities for more informed spectatorship.

Digital programs may also incorporate searchability mechanisms, allowing spectators to instantly locate specific words, phrases, and themes, and follow a non-linear reading pattern. By also supporting annotations, they invite audiences to record their impressions, insights, and reflections directly within the digital text. Should the creators of a performance seek to encourage a more collaborative experience, digital programs could evolve into dynamic forums where the public contributes to an expanding body of interpretative discourse through shared notes, generating a polyphonic dialogue of perspectives, inquiries, and interpretations. This joint architecture would, in some degree, parallel academic marginalia in printed texts, yet fundamentally forming a collective, fluid repository of audience reception. Reading a program can thus be radically redefined from a more individual and passive activity to a shared, participative practice.

Part of the collection of programs kept by the Center of Theatrical Documentation of the University of São Paulo (Photo: Esther Marinho Santana)

(Not) A Verdict

When I think about the shelves full of meticulously arranged printed programs at the Center for Theatrical Documentation or at the many archives that I have visited throughout my career, either in Brazil or abroad, and then look at the latest digital programs downloaded on my smartphone, I cannot help but feel a mix of melancholy and excitement. Programs have historically served as paramount ties between audiences and the transitory nature of performances… If theater is the art of presence, what can be more fitting than the palpable existence of an artifact that links us to a work that is extinguished the moment it is created?

However, the increasing popularity of digital programs in Brazil signifies more than a mere shift in medium. The Brazilian cultural context, with its many local economic constraints, social disparities, and institutional limitations, illuminates vaster questions about cost-effectiveness, accessibility, long-term preservation and dissemination, sustainability, and the evolution of theatrical experience in the digital age – issues that may resonate with readers in Hong Kong and other communities worldwide.

Time will tell the future of printed and digital programs. In this brief article, I tried to reflect on both positive and negative aspects of each format and rather than conceiving of the current transformation as a binary, mutually exclusive choice, I would personally prefer to see printed and digital programs coexist. As stages around the globe navigate this unstable terrain, we should consider that the reconfigurations of theater programs mirror the performing arts’ perpetual dialogue between tradition and transformation, ephemerality and permanence. The best route lies not in resisting changes, but in ensuring that new technological possibilities improve creative processes, the spectatorial experience, the safeguarding, and the memory of performing arts for us, spectators of today, and for the public of tomorrow.

[1] Pavis, Patrice. Dictionary of the Theatre: Terms, Concepts, and Analysis. Translated by Christine Shantz, University of Toronto Press, 1998.

[2] The Center of Theatrical Documentation of the University of São Paulo originated from the personal archives of professor, critic, actor, and set designer Clóvis Garcia. From the 2000s onwards, it has expanded its collections mainly through donations. Nowadays, it keeps a highly diverse array of items related to Brazilian theater and foreign theater in Brazil, from the 18th century to the present, such as programs, manuscripts, correspondence, diaries, photographs, audio files, maquettes, costumes, and props. Serving as a key institution for conservation, it also fosters research projects led by undergraduate and graduate students, as well as researchers, and professors of the University of São Paulo: https://www.cdtusp.com.br/

[3] Moura, Bruno de Freitas. “Uso de internet no país cresce mais entre idosos, aponta IBGE” [Internet Usage Grows More Among the Elderly, shows IBGE]. Agência Brasil, 16 Aug 2024, https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/geral/noticia/2024-08/uso-de-internet-no-pais-cresce-mais-entre-idosos-mostra-ibge

[4] Greshko, Michael. “Fire Devastates Brazil’s Oldest Science Museum”. National Geographic, 6 Sep. 2018, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/news-museu-nacional-fire-rio-de-janeiro-natural-history

[5] Rattle, Robert. Computing Our Way To Paradise?: The Role of Internet and Communication Technologies in Sustainable Consumption and Globalization. AltaMira Press, 2010.

[6] Ritche, Hannah; Roser, Max; and Rosado, Pablo. “Renewable Energy: Renewable energy sources are growing quickly and will play a vital role in tackling climate change”. Our World Data, January 2024, https://ourworldindata.org/renewable-energy

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。