In the face of the irresistible force of the changing global political climate, a sense of powerlessness is often evoked in the minds of individuals. This feeling will be further magnified when one’s homeland is lost or destroyed. Hudec is a theatre performance that studies the dramatic life of László Hudec, a notable Austria-Hungarian architect who survived through the two world wars. After World War One (“WWI”), his motherland Austria-Hungary was dissolved and succeeded by several states. Consequently, László became a stateless person and his identity got complicated.

The performance I attended was in October at the 2021 Wuzhen Theatre Festival. Hudec first premiered in Shanghai in March 2021 as a collaborative work of Shanghai Theatre Academy teachers and its recent graduates. The play was first written by Guo Chenzi and was directed by Coco Zhou. The 130-minutes performance was both documentary and ensemble devising in nature. The script was based on large amounts of historical documents and the performance text was credited to the collaborative work of the creative team. In the Wuzhen version, most of the cast, apart from two performers, retained their roles.

László’s story is told in two linear narratives. The main narrative was that László in his late fifties decided to move permanently to America and was being interrogated about his citizenship and his identity by an American immigration officer in minute details for three years. The supplementary narrative of László’s earlier life was interwoven into the main narrative when he answered his complicated citizenship and identity via a retelling of his past life. The supplementary narrative could be broken down into four stages: WWI, arriving in Shanghai, the death of Géza, his younger brother, and leaving Shanghai. Events of the supplementary narrative are clearly illustrated until the aftermath of Géza’s death. The latter events, in comparison, are fragmented and overshadowed by the climax in the main narrative.

However, this supplementary narrative makes up the bulk of the content and occupied nearly three-quarters of the performance length. The main narrative highlights the theme of citizenship and identity and serves as the thread to progress from one significant stage of László’s life to another. In comparison, the dramatic tension in the main narrative persists and builds up slowly and gradually. During the interrogation, László was on his best behavior. He was agitated once which he later quickly apologized to the immigration officer. Near the end of the interrogation, the dramatic tension of the main narrative sharply peaked when László was suspected of being a Communist spy. This was the revelation point that the interrogation had lasted for three years. If the main narrative is taken away, the supplementary narrative resembles an epic story that follows the journey of László from his childhood days. In the journey, László was helpless and pushed around by fortune. He could only react to the consequence of the global conflict in his best possible way. This sense of lonely rootless drifting on a volatile global stage is strongly conveyed to the audience.

The perception of this essence could be sharpened should the creative team removes the motif of Tower of Babel. At the start of the play, the ensemble cast told a biblical story in which God, upon seeing the tower, disrupted man’s single united tongue into different languages resulting in man incapable of understanding one another. The motif was repeated at the end of the play. Indeed, meaningful connections can be drawn, for instance, the volatile global conflict like God in the allegory disrupted László’s life; Christianity which was László belief and the Tower of Babel shared a Biblical origin; László who was an architect and the Tower of Babel belonged in the architecture category. Yet, this motif does not fit into the play due to heavy contradictions. First, conflicts in the play were not caused by different languages directly. On the contrary, language was never a challenge to László. In the play, László was talented in learning foreign languages. He acquired proficient mastery of the Russian language while he was a captive of the Russian Empire army. Secondly, buildings were the product of László attempting to positively change the world. In one of László's iconic lines, he described his job as an architect as “drawing a window here”. However, in the biblical myth, the Tower of Babel had a negative connotation. It was the source that leads to chaos and disorder. These connotations are at odds. As such, the placement of the Tower of Babel at the beginning of the play confuses the audience in understanding the play.

This minimalistic scenography is stylish and invites the audience to fill in the gaps using their imagination. Building, a theme in the play, was illustrated by contours on the set. The left side of the stage was like a modern art installation: two vertical flat slates sandwich a two-storey-tall tower at a right angle. The installation had two visible doorway openings positioned at the intersections between the slates and the tower. The two openings served as the main entrances and the exits for the performers. In contrast, the tower was utilized once in the exposition scene of World War Two ("WWII"). The rest of the space resembles an empty stage. On the planes of the installation and the back wall of the empty stage, words and graphics were projected to provide circumstances of the scenes, for example, the year and the location of a scene; the concerning sketches of important buildings designed by László. The projections are aesthetic pleasing, but their role in the performance is minor. Indeed, the projections of László’s sketches might have evoked a connection with the audience who have seen the actual buildings. However, no deeper or significant meanings are brought out from the projections. Perhaps the projection can occupy a more important status by giving the audience a glimpse of the landscape in the respective period because the time and the environment can better facilitate the understanding of László's journey.

Utilizing seventeen luggage to build the scene on the empty stage is an excellent creative choice because it captures the drifting and temporariness worldview of László. In the play, László was forced to leave his motherland by external global conflict. Although he had lived in Shanghai for a prolonged period, he had never settled in and longed to go back to his country of birth. The recurrent image of the luggage reinforces that László was a passer-by in China and was ready to leave at momentarily notice, regardless of how successful he was in Shanghai. Using the luggage as building blocks, the ensemble cast formed a working desk, a wooden crate, the Babylon tower, a model of the German Church, etc. This construction of the scene matches the fact that László was an architect. It also puts forward the idea that the landscape of Shanghai was temporary because this was not László’s home and that his buildings were fragile and cannot withstand the destructive power of states since some of his buildings were destroyed. The notion of ever-changing is conveyed by the simple props of luggage.

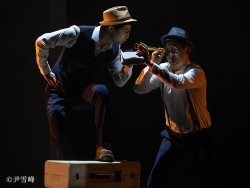

The feeling of ever-shifting is also delivered by the portrayal of multiple characters by each member of the ensemble cast. Each performer, apart from the male actor playing the oldest Hudec, was responsible for characterizing at least six distinct characters on stage with the help of full costumes. Furthermore, each performer was also required to play the role of a neutral narrator to brief the audience with information before each scene. As such, the performers adopted naturalistic acting for the characters and played a characterless narrator. Huang Fangling’s performance is the highlight of the ensemble cast. She was responsible for portraying at least nine different characters, such as László’s wife, László’s mother, a soldier, a translator, etc. In each of her portrayals, her clear physique and posture enabled the audience to quickly read her characters, especially for nameless characters like the soldier and translator. Her impressions of the characters were memorable and stood out from the cast. The performers embodying multiple roles further emphasizes the rapid changing of his surrounding people in László’s perspective. People in his life were passers-by and had not accompanied him for long. Only family members stayed with him for slightly longer because as the play developed his father and his younger brother who László shared a strong bond, all passed away due to sickness.

The ensemble performance as a whole is strong and enjoyable to watch. In dramatic scenes, the ensemble cast is capable of transforming the empty stage into a specific scenario, for instance, in the captive train scene, the ensemble cast played a band of captive soldiers doing various stage businesses in a square light zone; in the episode when László first arrived in Shanghai. Immediately, the audience realized the circumstances and could choose to follow the narrative or to investigate the characters' behaviors. During exposition scenes, the ensemble cast developed interesting ways to deliver boring but crucial information to the audience. One example is the dissolution of Austria-Hungary following WWI. In addition to the animated projection, to aid the audience in visualizing the historical action at play, the ensemble cast enacted a birthday party which included the actions of cutting a birthday cake and distributing the pieces to party participants. This presentation adds a new dimension in viewing the breaking down of László’s motherland as a bright new beginning. The unity and togetherness of the ensemble cast are best displayed in Hitler’s conquest in the WW2 scene. The ensemble cast following the beat of the music marched towards the right, the left and the right again. Through the unison movement, the audience can perceive the somberness and the destruction of the European continent brought by Hitler’s military operation. The cohesion of the ensemble cast successfully sets up the tone for the following scene.

The directing treatment the oldest László was controversial. Li Chuanying, who only played this role, does not belong to the ensemble cast. His portrayal of the character is stoic and controlled. His character only appeared in the main narrative and was the subject designed for the audience to empathize with. His main character's motive of clarifying his nationality and past deeds while sitting at the upper stage right corner did not help him to win over the audience's support or sympathy. Besides, in the supplementary narrative, all of the ensemble cast, but Huang, played various versions of László who were at different stages of his past life. It is more likely for the audience to identify themselves as the younger versions of László than the oldest version portrayed by Li.

The creative choice of portraying László by multiple performers is understandable. After all, the central theme of the play is questioning László's identity and investigating how the volatile external climate had continuingly shaped him into another person. The play tries to create a scene that juxtaposed the thoughts and beliefs of four Lászlós who represent his four main stages. Yet, the play fails in the delivery because the four Lászlós are not fully fleshed out since the foils playing against the Lászlós are weak.

Currently, the play focuses more on displaying László getting past the problems caused by the external environment instead of overcoming them. In the play, there are obstacles and internal struggles, but they have not left an impressionable mark in the minds of the audience. The supplementary narrative, which served as a summary to answer the interrogation in the scene, might be the cause. There are no worthy opponents embodying the forces or effects of the external political environment to László. In simpler terms, the characterization in the play is shallow. László’s acquaintances and collaborators are obscured and often forgettable. In comparison, László’s family members are characterized deeper. To illustrate the point, László’s brother and László’s father are used as examples.

The clearest antagonist of the play is Géza, László’s younger brother who only briefly appears in the play. In the play, Géza, a follower of Hedonism, was kind and enjoyed life while László was a serious authoritarian workaholic. László wanted Géza to work for him to learn his practice. However, Géza was uninterested and preferred to play musical instruments and had fun instead. Géza, as brother-in-law, bonded closer to László’s wife. This resulted in László becoming slightly jealous and sparking a row with Géza. Unfortunately, Géza grew ill suddenly and quickly died. László reflected on Géza’s death and became a better person by adopting some of Géza’s outlook, for instance, László spent more time with his family and pursued his preferred style of architectural design instead of merely fulfilling the demands of his clients. These alterations were emphasized on stage by changing the performer playing László to another. Through characters being at odds, both the characters of Géza and László are drawn out more clearly.

György, László's influential father, is underdeveloped. There were strong differences between the father and the son. László would like to become a priest while György wanted László to follow his steps and become an architect. Thus, György began training László at around nine years old. Without resistance, László followed his father’s arrangement. Hence, in the play, the sole function of György is to equip László with excellent architecture skills for succeeding in Shanghai. Referring to László’s biography, there are potentials to utilized György character fuller, such as teaching László responsibility to the family. In this way, György’s death ought to have far more significance than merely being an emotional impact on László. In line with the historical facts, László would have to take up the role of his father and become the breadwinner for his family which was experiencing financial difficulties. László wanting to return home will be against staying in Shanghai, a foreign land, to provide money to his family. Similar approaches can be adopted to develop the important characters who play foil against László.

Lastly, the absence of the immigration officer on stage is detrimental to the play. László was interrogated by a calm neutral voice-over in the performance. The originally tight tension is loosened as a consequence. Since the immigration officer is only an exposition and plot advancing device, there is no formidable adversary against László in the main narrative. The immigration officer had no stance, no attitude, represented no outlook or ideology. He was only performing his job as the servant of the state. Little is revealed about László in the interrogation process if the supplementary narrative is taken away. Perhaps the creative choice of not representing the immigration officer is to leave gaps for the audience to stand in the immigration officer's shoes to judge László. Yet, the play expects the audience to view the journey from László's perspective. These two angles of viewings clash, leaving the audience puzzled. Removing the body of the immigration officer costs a heavy price on the tight dramatic tension but generates unsatisfactory results.

In summary, both the playwright and director of Hudec have been too ambitious in the telling of László’s biography and in including too many themes. There are storytelling issues that require ironing, notably the characterization of characters in an epic story. The director had drawn inspiration from the National Theatre’s The Lehman Trilogy in producing Hudec, in terms of the ensemble cast acting style, each performer playing multiple characters and live music. Regrettably, the play is unable to reach the heights of The Lehman Trilogy. Nevertheless, the ensemble work of the cast was particularly well done and made the performance worthy to watch. With some revisions, Hudec has the potential of becoming an iconic Chinese documentary epic theatre piece that tells the first half of 20-century history from the eyes of László.

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。