Abstract: The concept of postdramatic theatre has raised discussions, inspired creative explorations and led to research in theatre in recent years. Through the review and reflections on two original medicine-themed site-specific performances created by the authors, The Hong Kong Plague of 1894 (2014) and Morbid Anatomy (2016), the interconnecting relationships among medicine, theatre and light and the potentiality of light in the era of postdramatic theatre are studied. The cross-disciplinary and cross-media flow in the network of medicine, theatre and light could evoke reflection, re-thinking and re-proposal on the concepts of medicine, contemporary theatre and its aesthetics.

Since the publication of Postdramatic Theatre in 1999, the conceptual framework of contemporary theatre proposed by Hans-Thies Lehmann in his ground-breaking work has sparked creative exploration and research. In the performances of postdramatic theatre, the aesthetics of dramatic theatre, notably representation, imitation, illusionary staged realities as a whole, predominance of dramatic action, character and plot, and primacy of text, are critically reflected and challenged.

This paradigm shift in postdramatic theatre could inspire new potentialities at the intersection of theatre and medicine. Light, an important visual component in performances–yet long subordinated to text, plot and character in dramatic theatre–could be emancipated thus gaining equal rights with other theatrical means including text, becoming autonomized and opening up new possibilities for medicine in/and theatre. Such potentialities at the junction of medicine, theatre and light in the era of postdramatic theatre were explored and examined in two recent original performances created by the authors, The Hong Kong Plague of 1894 (2014) and Morbid Anatomy (2016).

The Hong Kong Plague of 1894 (2014)

The Hong Kong Plague of 1894 was a site-specific performance in 2014, inspired by the history of the third plague pandemic outbreak in Tai Ping Shan District of Hong Kong, in 1894. The performance venue was a medical museum as well as the heritage site of the old colonial government bacteriology laboratory. The building is located in the centre of Tai Ping Shan district, the original site of the plague outbreak. This outbreak was medically and historically significant since Yersinia Pestis, the causative bacteria of plague, was first identified at that time. This was a milestone of modern microbiology development.

The outbreak also brought the conflicts between the colonial British and local Chinese communities regarding healthcare concepts and underlying politics to the surface. As medicine from the colonial British government finally ruled over the local practice of Chinese medicine, the outbreak set the scene for the predominance of Western medicine in Hong Kong, a dominance that persists today.

However, what had this historical event to do with contemporary audiences? If we critically examine the grand narrative of this plague outbreak, we arrive at several unsettling questions. Why does only the perspective from the British Colonial Government and Western Medicine appear in the historical records? Why were the Chinese blamed for poor hygiene and the plague outbreak? Who constructed the history and the medical knowledge? How and why were the history and medical knowledge constructed?

Such questions on the established narrative of the plague outbreak, and the reflections on Western medicine and its relationship with human bodies, human beings and the environment became the point of departure for the explorations in the devising creative process, and finally transformed into a performance with interplays of movement, light, space, texts (and their deconstruction), sounds and smells, but no plot or characters.

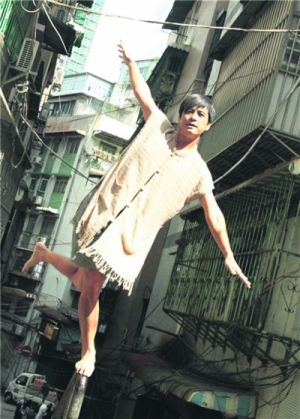

Before the performance, in order to arrive at the performance venue of the heritage medical museum, the audience had to pass through Tai Ping Shan district, with mixed historical traces and contemporary buildings. Once they entered from daylight into the dim performance space, they could smell a familiar yet unfamiliar odor produced by burning a mixture of sandalwood and frankincense, the fragrances recalling both Chinese and Western religious ceremonies as well as the mixed Chinese and Western environment in the district. The audience members were encouraged to move freely inside the performance space. They could find pages and images from medical journals scattered on the floor, while four performers gradually shifted from motionlessness and gentle breathing into slow movements and heavy breathing.

Light soon joined the performance in the form of electric torches held by the performers. In the presence of the smoke from the burning fragrances, the immaterial cool light beam became material. Together with the movements and voices of the performers, the material light and the shadows dissected, transformed and reconstructed the interior space of the heritage building. Light also passed through the thinner skin of the performers’ bodies revealing the interior space of human bodies. The torches themselves were transformed into the extended bodies of the performers, medical examination machines and the metaphor of (medical) authority.

In the next part, glaring and radiating cool white light replaced the electric torches filling the interior space from a white fluorescent light tube on a blackboard. The performers wrote on the blackboard and recited phrases of emotions and hints associated with plague and disease. The sound of writing on the blackboard was like a ticking clock. One of the performers attempted to break away from the confinement of the interior space to find the way out. As he removed the white gowns covering the window, daylight intruded into the interior space. But he could find only a barred window and the outer world far away.

The performers led the audience to move into another room of the building. The performers read out the medical information about pathogenesis of plague and Yersinia Pestis. The reading gradually became louder, fragmented and then hysterical. At the same time, the mechanical sounds of a typewriter and some slide projectors in the same space transformed the entire scene into a musical composition reflecting on the relationship between medical authority and human beings.

The Hong Kong Plague of 1894 (2014). (Photos by Fangönei)

Morbid Anatomy (2016)

Morbid Anatomy was a site-specific performance held in a pathology teaching laboratory, inside a local teaching hospital, in 2016. There was no clear-cut character attribution, no plot, no dramatic action, thus unsettling conventional dramatic forms. Instead, the structure of the performance was adapted directly from the actual medical practice of handling pathological specimens, so each section of the performance was titled “procedure” instead of “scene.” Light, space, sound, smell and movement, in a framework inspired by post-minimalistic musical composition, interacted to form the thematic narrative and transform into a major “performer”.

The performance looked into the inter-relationship among human beings, human bodies and the medical system mainly under the framework of pathology, a medical specialty combining pure science and clinical practice as well as the scientific basis of knowledge of all the medical specialties.

Before the performance began, the audience first gathered in the ground floor lobby of the main hospital building. After all members of the audience arrived, the producer led them through a route of a few-minute walk in which the group passed through different hospital facilities, encountering real-life hospital staff and patients, until they arrived at the main entrance of the pathology teaching laboratory.

The odor of alcohol welcomed the audience on entrance to the laboratory. The performer then entered. She was a practicing pathologist in real life and she “performed” the role of a pathologist in the performance. Different kinds of medical material were included in the performance, such as medical objects (human cancer cell line, pathology specimen bottles, medical textbooks), medical equipment (microscope, microscopic glass slides), medical texts (pathology texts, anatomical terms in Latin) and medical images, from old anatomy and surgical atlases as well as recent medical research.

This material transformed gradually yet radically during the course of performance. For example, pathology specimen bottles became musical instruments; morphology of human cancer cell line cells were reimagined as landscape and medical texts were reimagined as music. Every laboratory bench became the main stage for each “procedure” where light and space, light-transmitting objects (table lamp, laser scanner, PAR theatrical lighting fixture, neon light, video projector, red flashlight, tungsten light bulbs), transformed medical material, prose-like texts, sound and movements juxtaposed and intersected to form a post-minimalistic musical composition.

The audience members travelled from bench to bench with the performer through the space of the laboratory. Through the dramaturgical composition, in which different theatrical means were of equal rights, the ideas involving medicine and human beings, such as the construction of medical knowledge, medical system, medical gaze, human bodies and immortality were examined and reflected upon anew.

Morbid Anatomy (2016). (Photos by Fangönei)

Bidirectional Relationship of Medicine and Theatre

Both The Hong Kong Plague of 1894 and Morbid Anatomy performances are strongly medicine-related. Western medicine and its relationship with human beings are the core themes under critical examination in both performances. Medicine-related material including the history of the plague outbreak, pathology practice, medical knowledge, medical space, medical texts, medical objects and medical equipment become inspirations for the creative processes, and express the artists’ hope to raise the awareness of the audiences on medicine-related issues and provoke their reflections on the topics.

However, this relationship is not merely unidirectional, such that theatre acts only as a means to examine and reflect on the concepts of medicine. The transformation of routine pathology procedures into performance allows Morbid Anatomy to break away from the predominance of narrative text, plot, dramatic action and character in dramatic theatre.

In The Hong Kong Plague of 1894, medical information about pathogenesis of plague and bacteria are read out repeatedly with gradual fragmentation and random reconstruction of sentences, and the reading changes from normal tone of voice to hysterical expression and opera-like singing. Near the end, the medical words are present acoustically but the medical context is abolished. Medical texts become sound with shift and loss of context and meanings.

In Morbid Anatomy, the anatomical terms in Latin are recited live as well as played back using a cassette tape player. These Latin terms, which are normally spoken with English pronunciation in daily medical practice, are recited in the performance with Latin pronunciation. The change in pronunciation practice of the anatomical terms connects them to their history, but, also, becomes foreign from modern medicine and transforms them into mere sounds thus losing the modern medical context. Such reinterpretation and deconstruction of medical texts transforms the texts into musical composition, and shifts both performances away from the primacy of texts, while it questions the authority of these medical texts and the underlying power structure of medical knowledge.

Another major musical moment in Morbid Anatomy is inspired by and adapted from the registration procedure of pathology specimens in daily pathology practice. The rhythm of light emitted from a laser scanner and distorted by the pathology specimen bottles, the rhythmic sound of the pathology specimen bottles and metal trays placed on the bench and the series of numbers recited by the performer transform this part of performance into a piece of minimalistic music. The minimalistic musicality of the performance, inspired by medical practice, criticizes the industrialized and mechanistic daily routines in most medical specialties. Medicine becomes an alternative means to explore new possibilities of the aesthetics of performance with reference to the concepts of postdramatic theatre; the alternatively explored aesthetics thus becomes a critique to medicine itself.

The Potentiality of Light at the Intersection of Medicine and Theatre

One of the aesthetic characteristics of postdramatic theatre is the challenge and rejection of the primacy of text. Through gaining equal rights with other theatrical means including text, light becomes autonomized and opens new possibilities in performance, which are unimaginable in the logocentric hierarchy of dramatic theatre. In both of our performances, light attains autonomy through the constellation of aesthetic features, the musicality of light being one of them. The concept of musicality of light is inspired by composed theatre, which brings reflection on the musicality of postdramatic performance forward to a paradigm shift in the creative process by applying the musical notion of composing to the theatrical aspects of performing and staging, and in our case, light particularly.

The musicality of light in our performances draws inspiration from various musical concepts, such as musical forms, and the concepts of time, space and color in music. The resultant complex rhythmic light composition of electric torches, in The Hong Kong Plague of 1894, and table lamp, laser scanner, red flashlights and tungsten light bulbs, in Morbid Anatomy, show the potential of the musicality of visual media in performance.

Both performances explore and experiment with metaphors of light and light objects. The electric torches as medical examination and authority, in The Hong Kong Plague of 1894, the table lamp as both the oppressor and the oppressed, and arrays of red flashlights as heartbeat, pathological specimens, death and life, in Morbid Anatomy, are some examples of these metaphors. Rather than delivering fixed meanings and grand medical narratives to the audience unidirectionally, these metaphors are the means to open up the performances for audiences’ participation in interpretation and to provoke the audiences to reflect critically on the medical themes of both performances.

The openness of performances in the framework of postdramatic theatre provokes audiences to become the co-authors and the active interpreters of the performances. This provocation of co-authorship and active interpretation allows more in-depth reflection by the audiences on the medical themes of the performances when compared to the unidirectional delivery of the concepts on medical issues in more narrative-dominated and logocentric performances.

In the form of postdramatic theatre, with no constraints from the text-centered and representational dramatic theatre, the perceptual and experiential potential of light re-emerges: the immaterial and material light beam from electric torches and the glare of the cool white fluorescent light tube on the blackboard, in The Hong Kong Plague of 1894; the weirdness of the light refracted and interacting with pathology specimen bottles and clear fluid inside; the dazzling and threatening reflections of light on stainless steel board and surgical tools from the punch illumination of the PAR theatrical lighting fixture; the immersive yet confrontational video projection; the invasive neon light out of the prolonged dimness; and the warmth and liveliness of tungsten light surrounded by coolness of space, in Morbid Anatomy. The perceptual quality of light significantly affects audience perception and reception of the performances.

The perceptual quality of light synergizes further with the site-specific nature of both performances. The non-conventional theatrical space together with the strong experiential nature of light engaged the audiences directly in a perceptual experience. In the non-conventional setting of the two performances, the audiences could move freely around the performance space of The Hong Kong Plague of 1894, or travel with the flow of the performance in the physical space of a laboratory, in Morbid Anatomy. The audiences were called to be aware of their own presence at an event and, therefore, able to engage with the actions performed around them through their heightened bodily perception capacities within this postdramatic context. The audiences may have been able to feel themselves part of the performance and interpret and reflect through this awareness on medical issues in our case. This audience experience of sharing light and space with the performers reinforces the concept of postdramatic theatre as ‘shared’ space (Lehmann, 2006: 122-5). Such a notion could be expanded to be “shared light-space,” as seen in both performances.

Through the constellation of aesthetic characteristics of light, including musicality, openness and shared light-space, together with the site-specific nature of the performances, a dramaturgy of light from a phenomenological perspective is established. The dramaturgy of light criticizes not only the narrative predominance and logocentricity of dramatic theatre, but also the power structure of modern medicine. Under the medical gaze, patients are objectified and reduced to a visual constitution of signs, symptoms, autopsy findings, pathological features and radiological images. Foucault underlines the sovereignty of eye and gaze over light: “All light has passed over into the thin flame of the eye, which now flickers around solid objects and, in so doing, establishes their place and form” (Foucault, 2003: xiv).

In this sense, light is restricted to a limited space under the power of gaze and loses its autonomy, like light confined on the stage of dramatic theatre while the audience sits in the dark. However, with the dramaturgy of light, light achieves a state of autonomy; it is no longer confined to the reign of gaze and the constraint of dramatic stage.

In our performances, light travels through different places and spills into the spaces in between; it is inside the performers, the audiences and the spaces in between; it is in both visual and musical spaces; it remains largely outside of the texts, although sometimes stays beside them; it is in the present and travels simultaneously into the past and the future of human beings inside the medical system. It wanders the medical and artistic spaces oscillating between theatre and medicine.

It is a light radiating in multiple dimensions. The cross-disciplinary and cross-medial flow in the network of medicine, theatre and light could evoke reflection on and reassessment of the concepts of medicine, contemporary theatre and its aesthetics.

Works Cited

Eco, Umberto. The Open Work. Trans. Anna Cancogni. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1989. Print.

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic: An Archeology of Medical Perception. Trans. A. M. Sheridan. London: Routledge, 1997. Print.

Lehmann, Hans-Thies. Postdramatic Theatre. Trans. Karen Jürs-Munby. London; New York: Routledge, 2006. Print.

Newman, J. O. “The Phenomenology of Non-Theatre Sites on Audience.” Theatre Notebook 66, no. 1 (2009): 48-60. Print.

Roesner, David. “Composed Theatre in Context.” Composed Theatre: Aesthetics, Practices, Processes. Ed. Matthias Rebstock and David Roesner. 9-16. Bristol, UK: Intellect, 2012. Print.

*The article is originally published on http://www.critical-stages.org/17/medicine-theatre-and-light-in-the-era-of-postdramatic-theatre/

(原載於June/Juin 2018: Issue No 17《Critical Stages/Scènes Critiques》)

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。